2021年6月29日 星期二

It has been 9 whole years

2012年10月5日 星期五

2012年8月24日 星期五

Brain vs Brawn, Monocle issue 56, vol 6

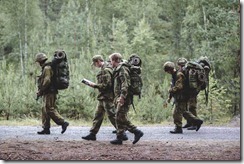

In the world of chaos differs with world war 1 and 2, those holding rifles and wearing helmet are required not just muscles to killl and shoot, but more on mental endurance.

Writer: Steve Bloomfield

Photographer: Thomas Ekström

Sat on his heavy backpack, slumped forward with his head in his hands, Espen Jorgenson wears the look of a defeated man. His face is caked in mud, his eyes are empty. Moments ago he had been marching through this beautiful Norwegian pine forest, the sound of birdsong mingling with distant gunfire, the picture of determination – the picture, in fact, of the modern Norwegian army: tall and blond, young and resolute.

Part of a 1,000-plus team of would-be recruits at the Norwegian Army’s officer training school, Jorgensen, a gangly 19-year-old, had been leading a team of seven other teenagers, marching up hills, dragging tired and broken bodies through rivers, marching down hills, heaving sandbags, lifting tree trunks, marching up hills again. He had been doing this for three weeks, rising at 06.00 every morning, falling, exhausted, into a sleeping bag at 02.00 every night. Friends had dropped out every day. More than 5,000 had applied, 2,500 had been invited for interviews, 1,700 had turned up on day one, 950 were now left. Jorgensen wanted to be one of those who made it to the end, one of those who was given one of the 673 places the Norwegian army awards each year to the men and women it believes have what it takes to be officers in arguably the world’s most professional modern fighting force.

It was not the physical exertion that broke Jorgensen: it was a picture and a story. Faced with an image of dead soldiers and asked to consider leading his friends into a situation where one of them might die – or might have to kill – Jorgensen realised it was over. “I knew there and then I couldn’t be that guy,” he says. “I’m tired and hungry, my feet are covered in blisters. The motivation has gone. I’m in the wrong place.”

Every summer at this former military camp in the forest of Evjemoen, an hour’s drive north of Kristiansand, Norway picks its best and brightest – not necessarily its biggest. “It’s not about who’s strongest, who’s fittest, who’s got the loudest mouth: it’s about iq,” says Alexander Hage, a senior officer who tackled the course himself in 2005. “We need the muscle but the muscle is easier to train.”

The muscle gets a decent workout nonetheless. It is physically gruelling, relentlessly so. Yet those who fall by the wayside aren’t necessarily the least fit – the white marquee filled with dropouts waiting for the bus back to the airbase has four occupants by midday, all of them male, all of them tall, all of them clearly stronger than the average citizen. Meanwhile, deep in the forest, 1.5m-tall teenage girls are still going strong.

The mind, though, is what really matters. Split into groups of eight, the recruits perform at least half a dozen set tasks a day, with a different person taking on the role of team leader each time. It is a cloudy July morning and seven teams are attempting to get themselves and their heavy backpacks across a five-metre gap, supposedly full of landmines using just five large sticks and a piece of rope. They are overseen by a handful of selectors – young army officers who a few years ago went through this training course themselves. As the recruits find new and creative ways to fail (sticks collapse; ropes slip from hands; three “die” when a makeshift bridge topples over), two of the selectors, Lieutenants Emil Ottosen and Bjorn-Otto Morfjord make a half-hearted attempt to suppress smirks.

Ottosen (small and round) and Morfjord (tall and skinny) make a good double act. They happily mock their charges: as a team leader struggles to corral his group into some sort of formation, Morfjord mutters, “I’m very uncertain if I want him to pass or not,” while Ottosen gleefully points out mistakes: “That’s an error,” he says excitedly as a structure of sticks and ropes falls apart. “That’s an error right there!”

And they’re not above mocking their country’s ideals either – as another team endlessly discuss how they’re going to tackle the next task, Ottosen bellows “Long live social democracy!”

Norway’s liberal politics have a major bearing on how the country’s armed forces operate. It is a country where the military has played a far larger role in its recent history than is the case for many other western nations. Occupied by Germany during the Second World War, under constant threat from the Soviet Union along its 196km-long border throughout the Cold War, Norway has over the past two decades slowly adjusted to the new realities, taking on peacekeeping roles in two continents.

There is a Norwegian presence in Afghanistan but Lt Col Sven Olan Berg, the imposing steel-blue-eyed head of the training programme, makes it very clear what he is looking for in an officer sent to serve there, while subtly suggesting Norway’s partners may not always be thinking as carefully. “We want people who can go out in other countries and cooperate with them – not just stand behind a wall and shoot anything that moves.”

For Berg and his colleagues the operation in Afghanistan is part of a bigger question to consider: what is an armed force actually for? For the first time in modern history, most western countries neither fear invasion nor have any imperial ambitions. For Norway, says Berg, the armed forces’ main role is to “defend democracy and our values”. The recruits who impress him are those who “want to make a difference”, he says, sounding more like he’s looking for ngo workers than soldiers.

They used to prefer signing up “a guy with a big physique, who would put a bag on his back and head into the woods to fight the Russians,” says Ottosen. Now Ottosen and his colleagues are looking for the sort of officer comfortable leading peacekeeping operations in Kosovo, drilling for water in Chad or working with engineers in Iraq.

That search involves testing their ability to deal with unexpected situations. In a small clearing by the side of a dirt track the leaders of seven teams are being briefed by Captain Per-Roe Petlund, a 20-year army veteran with a grey goatee, tobacco pipe and wooden staff. As Petlund explains their task – to put together a series of tents in preparation for the arrival of a group of war wounded – the rest of the teams are sat on their backpacks taking a rest. Some gnaw gingerly at their ration packs (they only have one meal a day each), others close their eyes. As Petlund sends the leaders back to their teams he points to the road – it’s booby-trapped, he says. Whatever you do, don’t cross it.

As the teams carry out their task the atmosphere is relaxed. Petlund lights his pipe, leans on his staff and grins. “I’m going to create chaos,” he says, with undisguised glee. A few minutes pass. Then, a blood-curdling scream from beyond the trees. Wounded soldiers begin appearing, each one more hysterical than the next. Their colleagues are trapped on the other side of the road, they scream. They’re all going to die. They must be saved. Some recruits panic, forgetting the instruction about the booby-trapped road and allow themselves to be dragged off to certain death. Others react with hysteria, angrily yelling at the wounded in a doomed attempt to calm them down. Petlund puffs on his pipe, watching closely.

“I remember this one well,” says Hage, with a grimace. “They have no idea what day it is, the competition is high, they’re being evaluated all the time.” Sometimes, he points out, they just crack. Eventually, as some groups manage to put up their tents and others begin to get slightly too aggressive in their attempts to prevent the wounded disrupting their plans (there have been broken limbs before), Petlund calls time.

He calls the recruits together, his face furious. “What were you thinking?” he bellows. “Your fellow soldiers, your fellow countrymen were in danger over the road! All of them could die! Why didn’t you save them?” A timid arm rises. “Because you said the road was booby-trapped?” offers a small voice at the back. “Excellent,” beams Petlund.

By the end of the day the incongruously beautiful pine forest is littered with clusters of exhausted teenagers in green fatigues. A group of 10 is sat in a clearing, eyes dazed; a dozen are collapsed on backpacks up the side of a hill; another 20 are marching down the slope, propelled as much by gravity as a sense of purpose, heavy feet slapping down.

“It’s a sign you’re getting old when you start feeling sorry for them,” smiles Berg, as he watches a group of recruits haul sandbags up a hill. This, he says, is the best year yet. “Now we say no to people that three years ago we would have taken in.”

As the recruits prepare for their final day, those that remain are determined to last the distance. “Sometimes I just want to cry,” says 19-year-old Martin Khorami, as he rests, briefly, in between exercises. “I’m starving and I’ve not had much sleep. But I’m very proud.” He grins, picks up his gun and jogs off. Another member of his team, Maria Orlandi, adjusts her slightly skew-whiff helmet and hauls on her backpack, ready for yet another speed march – or jagermarch. “I didn’t think I’d stay this long,” she says. “But I’m here. I’m still here.” — (m)

2012年5月20日 星期日

2012年3月4日 星期日

choosen

Livability. whether it is livable has numerous objective criteria; hours of sunlight per year, numbers of chain stores, politics, city development, max hours of working etc. …. but the word can only be represented when personal charming factor adds into judging.

Hong Kong has efficient transportation. From cityscape to scenery a 15 mins ride is possible; Hong Kong has a variety of food to choose, priced from $50 to $5000; Hong Kong is a place that possess night life, it just never stops in holidays that makes 24 hours a bit too short.

------------------

Yet when work has occupied a person for over 60 hours a week, it just doesn’t let people to rest and enjoy those benefits of Hong Kong, the place is not charming at all.

Chosen to leave.

2012年2月24日 星期五

Essay : On Charm by Stephen Bayley

I’ll tell you one thing you never hear. it’s this. ‘ I wish I were less charming.’ Aiming to wound, a schoolmaster wrote on my last report.’Charm alone will not get him through'.’ Meaning, I think, that an affable, genial, out-going nature was not enough to ensure survivial in a harsh world of statistical performance that even then was becoming dominated by dreary accountants and bland consultants.

In people, charm is an attractive asset (if not to my scrofulous, beetle-browed and negativist careers master). How else did the expression ‘ charm the pants off’ pass into currency ? People whose interpersonal skills are based on the reading of a P&L account are rarely said to possess such mysterious and fascinating powers of undress. ‘He could double-entry book-keep the pants off anyone’ is another thing you never, ever hear. Charm is disable and unscientific, powerful but measurable, hence disturbingly threatening to the management mentality.

We often see in the buildings or places or things, characteristics which we call ‘charm’. The french government’s guide to hotels even has a category called ‘ hotel de charme’. Clue: ivy, geraniums in pots, open fire, direct-line to peasant or historic associations. London’s tourist authority describes Covent Garden’s Lamb & Flag as a ‘charming pub’. Clue: ivy, geraniums and so on. In architecture and products, its is always easy to detect charm, if not to define it. I suspect it is something to do with the curious relationship between accident and design. Charm is often a result of the former. Put it this way: John Pawson’s superlative Novy Dvur monastery is beautiful and many other lovely things but it is not charming. It is too fine for that.

Or put it this way: a grumbling Porsche Neunelfer may be a desirable and fine car, but if performance were calibrated in charm, it would fall far behind a Morris Minor. Power is rarely charming; vulnerability always is. Dinner at Alain Ducasse in Monte Carlo? Very impressive but cold. A beer in Vienna’s Cafe Preukl where you can still smoke and the furniture has not changed since about 1959? Chaotic but intensely charming. Or gemütlich, as they say in Austro-German.

It all comes from the Greek notion of charisma – that compelling attractiveness certain people have that inspires devotion, something which sociologist Max Weber picked up and popularised in his study of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The very charismatic Albert Camus believed that charm gets you to a (pants off?) position of ‘yes’ without having actually asked a question.

Perhaps as a result, people are suspicious of charm. Anita Loos, for example, called pubic relations ‘fake charm’. Because it is so powerful, but also so unaccountable, charm is a powerful eapon in the battle against the bureaucratic consultant was by Alred Mckinsey, whose drab successors with their one-dimensional view of the world and bad suits still dominate government and business. McKinsey said, you can measure anything. And if you can measure it, you can manage it. Like my schoolmaster, McKinsey was 100 per cent wrong. You cannot measure beauty, love, happiness or peace. You can only measure boring things.

In business as well as perosnal life, all negotiations are based on infrastructure where, during the date or the ptich, power creeps from one side to the next. Winning is a matter of emotions, not measurement. That’s why charm alone will get you through.

2012年2月8日 星期三

Limit

I have been saying for a long time about my work

6 years is a maximum

Passing the coming september will be my fifth year. Yet I am feeling the end arrived as if it were tomorrow. I desperately need a change.

I am drained.